The musical history of Carroll County is filled with many names of musicians who have garnered major local significance, national notoriety, or both.

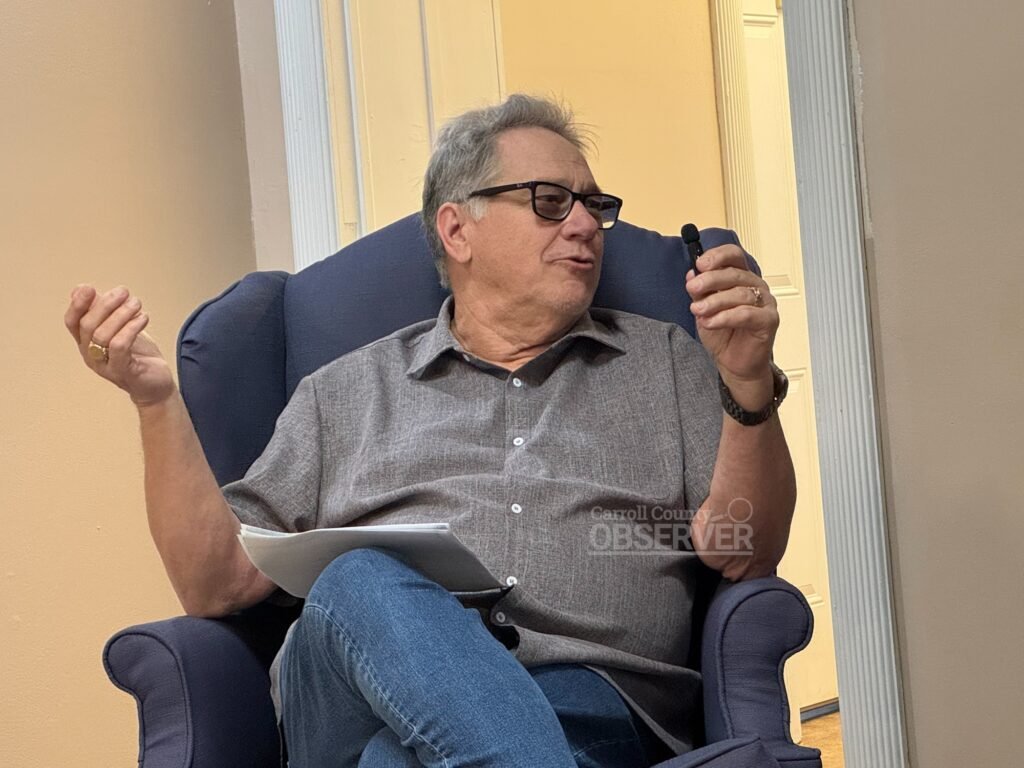

On Wednesday morning, Huntingdon Historical Society President Johnny McClure sat down with two of those musicians: Carl Byars of Huntingdon and Donald Carnell, a Clarksburg native. The three held a wide-ranging conversation about the vast, and largely undocumented, music scene that flourished across Carroll County from the late 1950s through the 1980s and beyond.

From Roy Rogers to the Beatles

Both Byars and Carnell came of age in the early 1960s, when television and radio were flooding living rooms with Elvis Presley, Carl Perkins, and the early stirrings of the British Invasion.

“You’d get home from school and there’d be one of those music programs on,” Byars recalled.

He was, of course, referencing shows such as Dick Clark’s American Bandstand and Where the Action Is.

“That’s kind of what put the bug in there,” he added.

Carnell said he got hooked on music at around age 10, when his mother would take him to square dances, where a local group called the Midnight Ramblers, featuring Sammy Butler, James Ray Sanders, Larry McDowell, and Tommy Cisco, performed. He also had fond memories of seeing musicians play at the Westport Community Center.

“What I remember most was the cake walks,” he said, “and seeing how all the girls liked the musicians. That’s what got me started.”

Byars started on guitar before switching to drums in high school, hauling his kit in the backseat of a 1959 Chevrolet on the theory that a gig might pop up anywhere. He also played in the school band.

Carnell’s path began when his father vetoed a drum set after one afternoon of practice, so he inherited an old Roy Rogers guitar from his Aunt Louise. He was a left-handed player trying to learn right-handed chords. His mother contected a local radio DJ, and set Carnell up with his first guitar lesson.

He made a four-mile bicycle ride on a gravel road to get that first lesson.

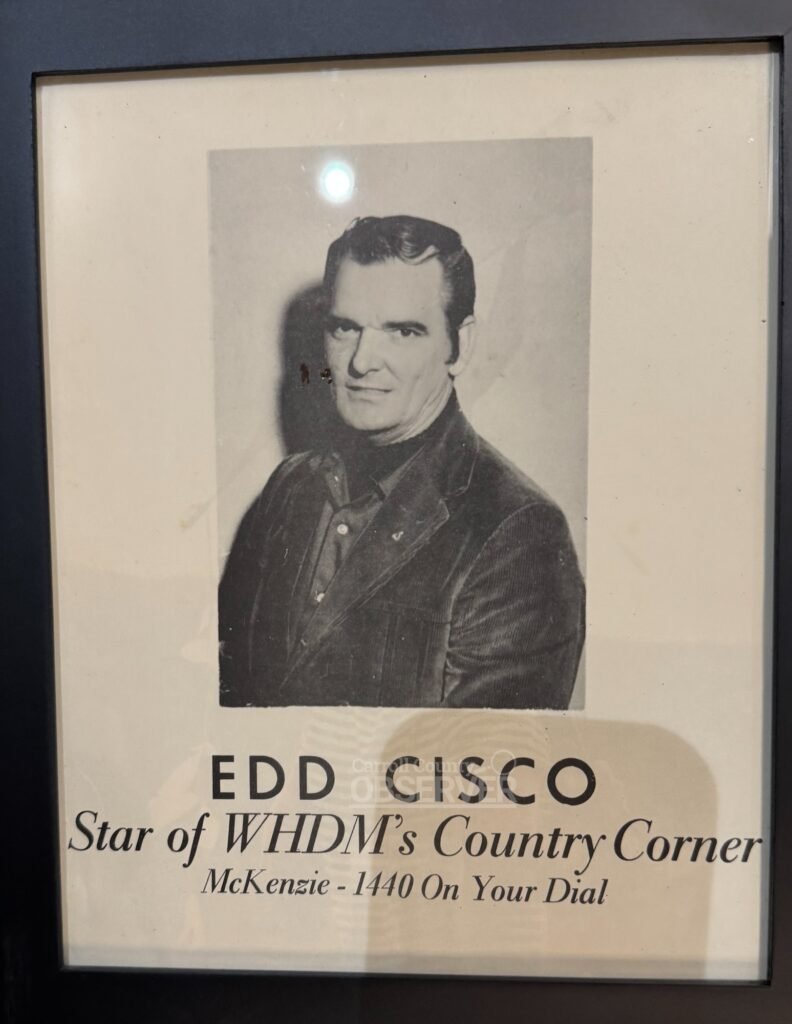

Edd Cisco and the Sound of the Radio

That DJ was Edd Cisco, who started out on WHDM and later moved to an FM station. He was known throughout the county as something of a gateway figure for aspiring musicians.

Before his broadcasting days, Cisco had performed under the stage name Eddie Starr, serving as a front man for Hank Snow. He later played rhythm guitar for Carl Perkins after Perkins’s brother was injured in an automobile accident.

Carnell described cycling down a gravel road as a boy to show Cisco what he knew on guitar, only to be gently informed that left-handed chord shapes would not do.

Years later, Carnell and Tommy Cisco, Ed’s son, would spend Saturday mornings at the radio station answering listener request lines after playing gigs the night before. Carnell recalled one particularly memorable morning, when a flood of requests came in for a then-controversial song called “The Lord Knows I’m Drinking” by Cal Smith. Ed Cisco played it anyway, over the program director’s objections.

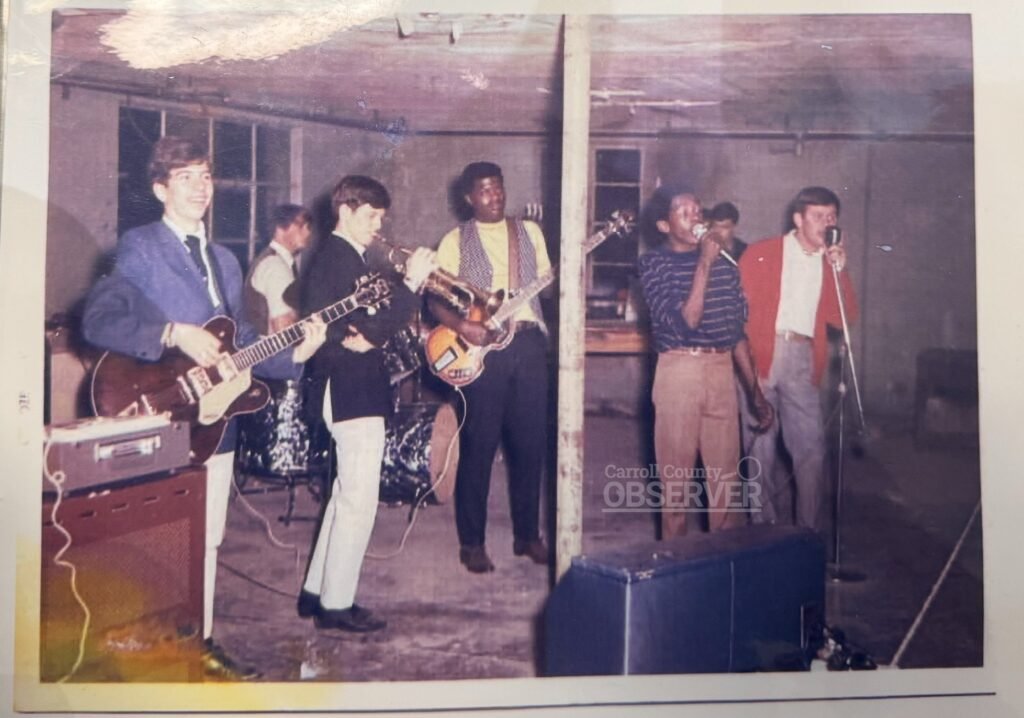

The Underground, the Armory, and the Bowling Alley

Young musicians in Huntingdon and Carroll County found creative solutions to the problem of where to play when they were too young for the clubs.

One of the most inventive was a venue that came to be known simply as “the Underground”.

The venue was a cleaned-out commercial laundry basement beneath a building that stood where the Chamber of Commerce is today. Byars said he and a group of friends talked a property owner named Mr. Pug into letting them use the space.

Byars said Mr. Pug allowed them to play there as long as they had an adult to chaperone.

After everything was in place, Byars explained that they put on shows that became, by all accounts, genuinely popular. The building was later destroyed in the 1971 tornado.

Other early venues included the National Guard Armory in Huntingdon, where a rotating roster of local bands played teen dances every other week.

In McKenzie, a bowling alley that had removed some of its lanes to create a dance floor hosted Carnell and guitarist Max Bybee when the two were barely teenagers.

Asked how many songs they knew, Carnell laughed. “About twenty. We stretched it. When we ran out of songs, we’d say we got a request, then play one of the same songs again,” he said.

Between Memphis and Nashville

Byars explained that Carroll County was fortunate in its geography.

“We were sitting in a sweet spot between Nashville and Memphis,” he said.

That proximity made a difference, especially in the types of music that influenced local musicians. It also made a difference in who might show up in the area.

Carl Perkins, whose family lived near Westport during part of the 1970s, was known to drop in on local events.

Byars recalled a cake walk at the Westport community center where Perkins simply sat in with the band.

“It wasn’t uncommon,” he said. “It was a much smaller world back then.”

Byars and Carnell also discussed Carl Mann, the Huntington native who recorded at Sun Studio and charted nationally in the late 1950s.

Carnell shared that Mann’s recording of “Mona Lisa” had narrowly missed topping the charts because Conway Twitty recorded the same song almost simultaneously, and both versions had released within days of each other.

Mann and Byars later played together on several occasions, and Mann co-wrote country songs with guitarist Larry Keith. A historical marker honoring Mann now stands on High Street in Huntington.

On the Road

McClure asked both men about the most unusual places they had ever played.

Carnell didn’t hesitate talking about playing a gig at a hog sale.

“We sat up where they brought the hogs right by us,” he said.

Byars recalled playing a set at Discovery Park of America in Union City, where he found himself standing beside a Brontosaurus skeleton in the main hall.

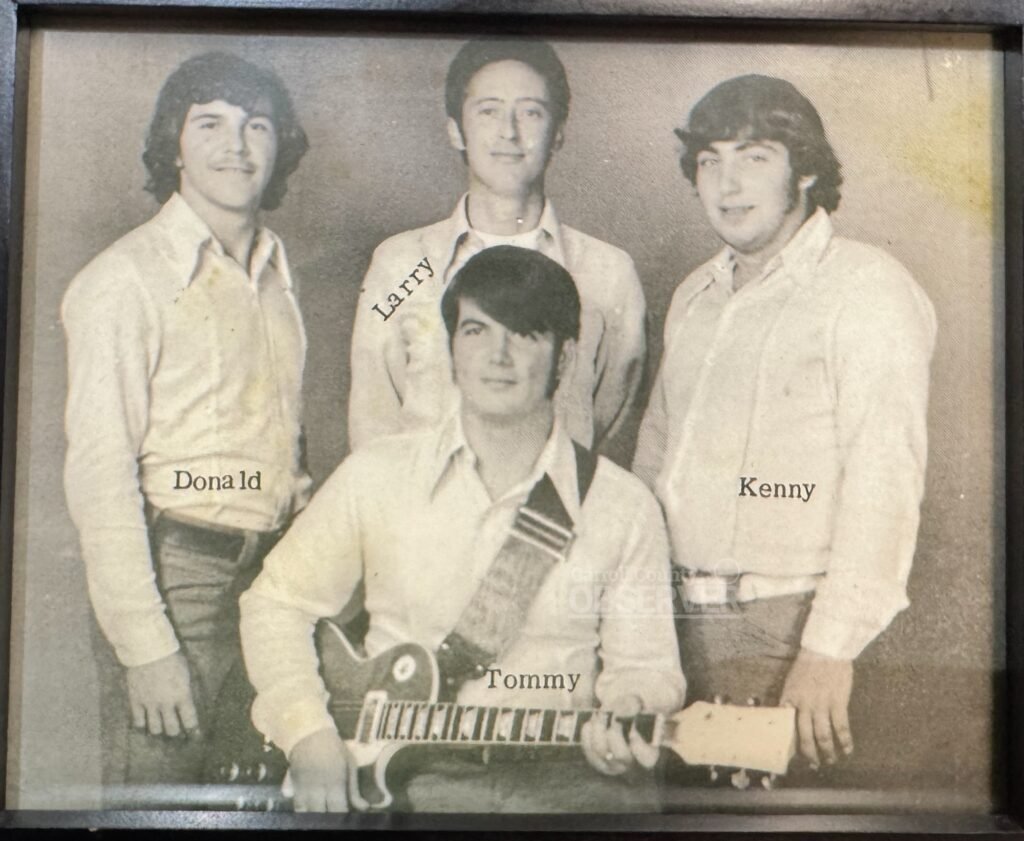

Carnell also discussed joining Tommy Cisco on the road after Cisco had signed a recording deal in 1977. He said none of them were older than 25 or had any experience navigating a tour bus on the interstates.

He told a story about driving through Atlanta, and there was a traffic jam while approaching the city.

Carnell said the band noticed an empty lane and pulled into it. He said other motorists made several “gestures” at them as they passed by on the empty lane. The band later realized they had been driving in the emergency lane.

“We had no idea!” he exclaimed. “We had never driven anywhere like that before.”

On another occasion, Carnell said the driver missed a turn in Mississippi and the bus ended up at the beach in Gulfport, roughly 60 miles away from their intended destination.

A separate run took them to a club right on Lake Ontario in Canada during February. Carnell recalled talking to his mom on the phone about it.

“Mom, you don’t know what cold is,” Carnell said he told her. “I don’t have enough clothes in my closet for this place.”

Playing for Yourself

Both men reflected on the long arc of a life in local music and the early years of believing that fame was just around the corner.

“Early on, we all think we’re going to be rich and famous,” Byars said. “Later on, it kind of settles into the fact that you’re just playing for yourself, playing for local people, playing for your friends. I often describe it as my hunting and fishing — I don’t hunt, I don’t fish, I just play guitar.”

During the COVID-19 pandemic, he played solo every Friday night at a local restaurant simply because there were no other gigs.

“If you’re going to play music, you have to be ready to change and do whatever,” he said.

Carnell credited persistence and good fortune in equal measure.

“I’m certainly not the best bass player in the world,” he said. “I was just in the right place at the right time, and I never gave up. I give it my all every time I played.”

Over the years, he estimated, he had shared stages with 65 or 70 national acts — Hank Williams Jr., Conway Twitty, Ronnie McDowell among them.

Keeping the Stories Alive

The conversation kept circling back to various names. Each one triggered another story, another connection, and thus another thread in a web of musical community that stretched across decades and a lot of gravel roads.

“One story triggers another,” McClure observed, and that seemed to be exactly the point.

The Huntingdon Historical Society’s monthly storytelling series was filmed by students in Hillary Clifft’s Social Media Marketing class at Carroll County Technical Center. They will post the video of McClure’s interview with Byars and Carnell to the Historical Society’s YouTube channel.

In March, former state representative Steve McDaniel will speak about the Battle of Parker’s Crossroads.